Editor’s note: This is part 4 of a series about Dixon’s remarkable role in the Civil War.

DIXON – I’ve lived most of my life in Dixon, but I had no idea of the significant role that Dixon played in the Civil War. Thanks to the 1892 “History of the 13th Illinois Infantry,” written by the soldiers themselves, I’ve now learned extensive specific details of their training time in Dixon and their many battles in the South. That book is the source for most of the information in this column.

Since the soldiers of the Illinois 13th were the first locals to join the war effort, they were ready for training before the government was fully ready to train them. For example, throughout much of their training in Dixon, many recruits had no guns.

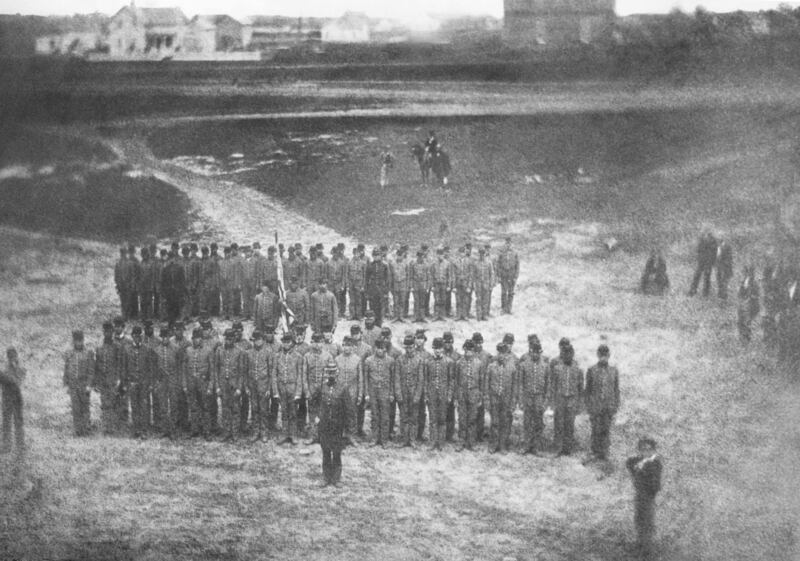

On May 10, 1861, guns were placed into the hands of only two of the regiment’s 10 companies. The history noted that Company B, filled with Sterling boys, didn’t receive their guns until May 23. Note that the photo shows no guns in Company B.

First wound

On the very first day when the eager soldiers were given guns with bayonets, the regiment incurred its first injury of the war. Company K, then known as the DuPage Rifles, was largely composed of “farmers and mechanics” from the area around Naperville and Downer’s Grove. Being the first to receive the guns, they were on guard in Dixon that day with the rifles.

When a soldier passed by, one young over-eager guard gave him “a lively bayonet jab in the abdomen.” The wounded soldier survived, but the incident became a reminder of the problem of “friendly fire.”

First fatality

The bayonet stabbing was not the only gun-related mishap that occurred in Dixon. A fatal incident occurred one night when 21-year-old Pvt. Frederick W. Brinkman was on guard duty near the spring that still runs along the east side of Oakwood Cemetery.

Guarding a training camp in Dixon was not a serious duty, because “there were no rebels to watch against.” Nonetheless, “Brinkman was not a man to be fooled with while on duty.”

His superior officer was Lt. N. Cooper Berry of Sterling. Although “only a boy in years,” Berry was “fiery and lacked judgment,” exhibiting a “tyrannical and overbearing disposition” that made him unpopular with the men. A perfect storm developed when these two young zealous soldiers clashed one night.

Halt! Who goes there?

Around midnight of June 14-15, 1861, Berry decided to inspect the guard posts. Approaching Pvt. Brinkman in the dark, Brinkman ordered Berry to halt and give the password. Berry refused, barking that Brinkman should know his voice.

Brinkman warned him three times to halt, but Berry continued to advance. The private then fired his weapon, and the musket ball passed directly through Berry’s neck, killing him instantly.

The private was immediately arrested but was returned to duty within a few hours. “Popular opinion sustained Brinkman, who was acknowledged to have done nothing but his duty.” He went on to serve his three years with the regiment and was deemed “a good soldier.”

N. Cooper Berry thus became the first fatality of the Civil War from this area. And it all happened in Dixon.

The first shock of reality

All 1,000 recruits (10 companies of 100) of the Illinois 13th Infantry thought that they would complete their service after 90 days and never leave the state. When they came into Dixon on May 9, 1861, they understood that they would defend the state of Illinois from rebel attack and return home by August.

But on May 22, a dispatch informed the regiment that the federal government wanted them for three years and, if they agreed, their service would send them to battlefields outside the state. They had only two days to decide their fate, because Capt. John Pope of the federal army was coming to Dixon on May 24 to officially muster in those who chose to proceed.

Each soldier of each company was free to make his own decision. Company A “was made up of the best class of young men of Dixon, and among its members were two doctors, seven lawyers and 39 who had taught school.” They faced a life-changing decision that would take them away from their Dixon families and jobs for years.

They ‘toed the scratch’

Stunned at the news, “there was considerable dissatisfaction among the men,” according to the “History of the 13th Illinois.” However, a spirit of patriotism and sacrifice swept through the camp, likely accompanied by a dose of competitive male bravado. Consequently, “the great majority toed the scratch and were in for the fight on good faith.”

The phrase “toe the scratch” was common at that time. It referred to the practice of scratching a line on the ground and placing your toe on the line to begin some competitive engagement. Thus, “toeing the line” or “toeing the scratch” meant that you’re willing to step up to the line and face the situation.

On May 24, 1861, Capt. Pope mustered 85 of the Dixon soldiers of Company A into federal service. After supper that evening, now as soldiers of the Union Army, the entire regiment formed a procession led by the Stars and Stripes – the U.S. flag, not the state flag. As the regiment’s musicians played, “they marched about playing and singing lively tunes.”

They had no idea that one of every five soldiers in the regiment would not survive the war. About 19 months later, the regiment would be in Vicksburg, Mississippi, facing their bloodiest day. We’ll tell the story of that fateful day in our next column on June 6.

- Dixon native Tom Wadsworth is a writer, speaker and occasional historian. He holds a Ph.D. in New Testament.